A brief overview

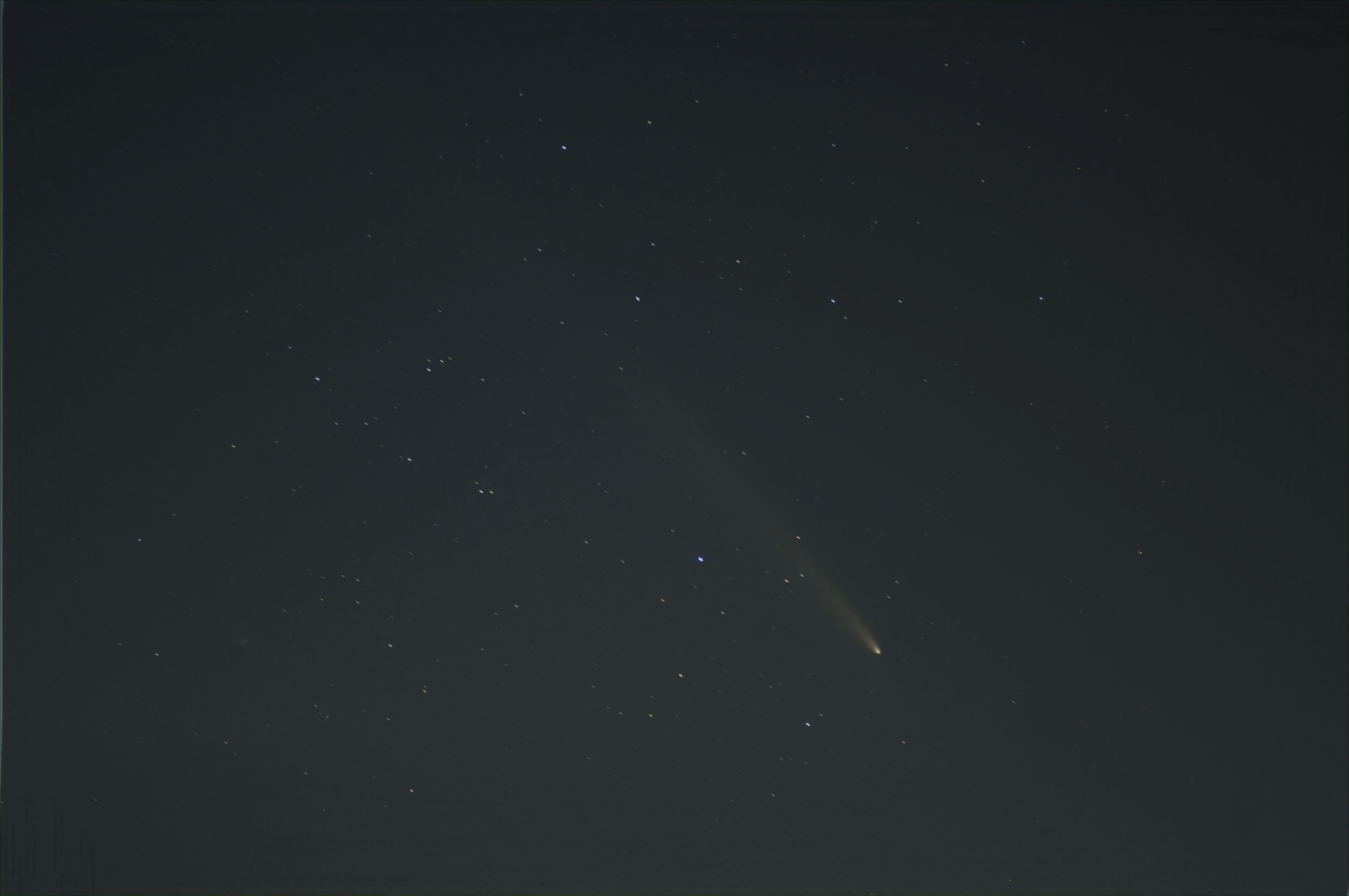

Dr. Achim Tegeler, October 2024

Comets have always stirred people's minds and led to amazement, ecstasy or fear. Until the Middle Ages, comets in Europe were regarded as harbingers of fateful events, as it was completely unclear where this new "hairy star" (ancient Greek. aster kometes] so quickly came from.

Apparently, however, the Babylonians were already in the 1st century BC. Able to observe comets and calculate a regular recurrence [1].

In Europe, Johannes Müller (lat. Regiomontanus) was the first in 1472 to try to calculate a comet's orbit. At that time, it was still not clear what the origin of comets was and whether they were in the near-Earth atmosphere. It was only the great Tycho Brahe who determined in 1577 that an observable comet must be at least 230 Earth radii away and therefore could not be at home in the Earth's atmosphere, but must be in space – a very controversial claim at the time, which Galileo apparently also contradicted.

Today we know that comets, as parts of our solar system, can penetrate into the inner solar system from the distant regions of the Kuiper Belt [2] and the Oort Cloud [3] and then travel back to the distant parts of the solar system after orbiting the sun. Some comets show an elliptical orbit that periodically brings them close to Earth. A distinction is made between long-period and short-period comets.

Long-period comets show an orbital period of more than 200 to several million years and come from the Oort Cloud. Depending on the closer encounters with the large planets, these orbits can then take on hyperbolic character (eccentricity >1) and never lead the comet towards the inner solar system again - such comets are then one-time visitors and may leave the solar system.

Short-period comets show a return in less than 200 years and usually come from the Kuiper Belt, i.e. an area of the outer solar system that is located in the plane of the ecliptic.

Many comets are discovered by monitoring systems, but some are also discovered by amateur astronomers. Whoever discovers a comet first can become part of the name of a comet, because comets (like asteroids) are named according to their own system.

Basically, a distinction is made between short-period and long-period comets (see above). For short-period comets, a P (periodic), for long-period comets a C (comet] is put in front of the name [4].

This is followed by the year of the first discovery and, as a letter code, the period of the year. The area A is in the first half of January, B in the second half of January, C in the first half of February and so on up to X for the first half of December and Y for the last half of December (I is not used).

If more than one comet is detected in one of these halves of the month, the sequential number is appended after the month number. After that, the name of the discoverer(s) is appended

For our comet C2023 A3 / Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, which can be observed so well in October 2024, this means:

C – it is a long-period comet

2023 A3 – it is the third comet discovered in the first half of January 2023

Tsuchinshan–ATLAS – The discovery was made at the Chinese Observatory on the Purple Mountain (Chinese: according to Wade-Giles: Tzu-chin-shan T’ien-wen-t’ai) near Nanjing in eastern China, about 200 km northwest of Shanghai – and was confirmed shortly afterwards by the Sutherland ATLAS System in South Africa (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) [5].

Since the discovery of the comet, it has been closely observed, and attempts are being made to calculate a course of the further journey of the celestial wanderer from the determined orbital data. It became clear that at perihelion (i.e. the closest point to the Sun on 27.09.2024), the Sun with its gravitational influence influences the initially hyperbolic orbit (no return) of the comet and changes it to a parabolic orbit (return possible). If the large planets do not change the comet's orbital parameters further, this comet should return to Earth in 240,000 to 3.5 million years.

Since these periods of time are neither imaginable nor "waitable" for us humans, we are all the more pleased to be able to witness the appearance of this comet!

By the way, comets leave dust and ice near the Sun with their tails. These residual particles remain on their orbit even after the comet has long since moved on and has not been observable from Earth for a long time. Some of the typical meteor showers (shooting star streams) such as the Perseids have their origin in exactly these comet tracks of dust and ice - > see also our report on the Perseids.

[1] Diodorus Siculus: Diodors von Sizilien historische Bibliothek. Band 3, Stuttgart 1838, S. 1368

[2] Kuiper belt https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kuiper_belt

[3] Oort cloud https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oort_cloud

[4] There are other preceding identifiers that can vary depending on the fate of the comet (X for comets with an unknown orbit, D for comets that no longer exist, A for asteroids wrongly considered a comet, I for an interstellar (otherwise unknown) object).

[5] ATLAS Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System https://atlas.fallingstar.com/