Remembering Beverly Turner Lynds

An article by Dr. Achim Tegeler, January 2025

The vast majority of astrophotos that are viewed in newspapers, on the Internet or at astronomy meetings show astronomical objects that stand out in the otherwise dark starry sky by their light. These are wonderful galaxies, coloured double stars, luminous nebulae that shine in H-alpha light, supernova remnants or planetary nebulae – all impressive objects that inspire with their colours and shapes.

However, anyone who deals with the formation of stars inevitably comes into contact with the optically rather inconspicuous, dark accumulations of gas and dust that represent the breeding ground of stars – dark clouds, also known as dark nebulae. These gigantic clouds contain so much matter in the form of hydrogen molecules (H2), dust and other gases in high particle densities that they do not allow the light from stars or glowing gases behind them to pass through and stand out (most recognizably) as dark shadows against a light background. The largest of these dark giants are irregularly shaped clouds with diameters of up to 150 light years, which carry millions of solar masses as matter.

Dark clouds are located in interstellar space and show a particle density that is 10,000 to 1,000,000 times higher than the surrounding space. The temperature in these dark clouds is very low (usually below 10 K – i.e. close to absolute zero) and favors the formation of molecules (H2) from hydrogen, which would be atomic (H) at higher temperatures.

About 1% of the mass in dark clouds is formed by dust, which consists of silicates, iron and carbon (e.g. graphite) and is surrounded by ice (frozen water, methane or ammonia). These dust particles are extremely small (between 0.01 and 0.3 μm) and therefore absorb light very effectively – the clouds therefore appear dark.

The presence of elements larger than hydrogen and/or helium is a clear indication that the matter in these dark clouds does not originate from the early post-Big Bang period, but from stars that have already passed away and have created these larger elements through fusion.

Some large dark nebulae can be seen with the naked eye because they are in front of brighter objects. This is how the dark areas of the Milky Way can be seen well on a clear summer night:

The fascinating thing about these dark clouds is that they provide the material supply for the formation of new stars. In the dark depths of these molecular clouds, matter gravitationally attracts each other and continues to condense by a factor of up to 1020.

Via intermediate stages that have collapsed to varying degrees due to gravity, such as the prestellar core, protostar and pre-main sequence star, the formation of a hydrogen-fusioning main sequence star then occurs – a topic that we will certainly consider separately in another article.

So dark clouds are anything but uninteresting!

The american astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard published the first catalogue of such dark nebulae in 1919 as the "Barnard Catalogue of Dark Markings in the Sky“ (182 objects) [1], and this was then published posthumously in 1927 by Frost, Calvert and Dobek as a revised new edition "A Photographic Atlas of Selected Regions of the Milky Way" with 369 photographed objects. This catalogue is still available as a book today [2].

In 1962, the astronomer Beverly Ann Turner Lynds [3] born in 1929, created a very comprehensive "Catalogue of Dark Nebulae" [4] after she gained access to the images of the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey of 1958 in the course of her work at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank.

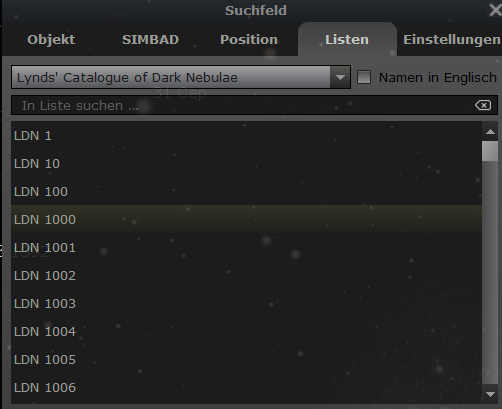

The images she had in front of her at the time in unprecedented quality clearly showed the dark fog. So she decided to search these images for dark nebulae and then compile them as a catalogue – this became the above-mentioned catalogue of dark nebulae, which, with its 1802 objects, is still considered by many to be the benchmark for working on dark nebulae today. For example, in the Stellarium software, which is used by many amateur astronomers, it is possible to search in the Lynds catalogue (LDN and LBN numbers) and also in the Barnard catalogue (B numbers).

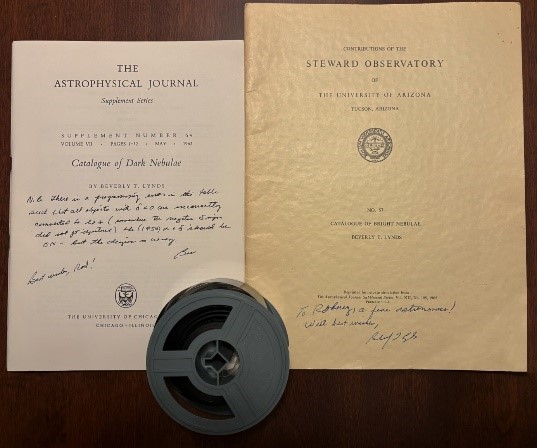

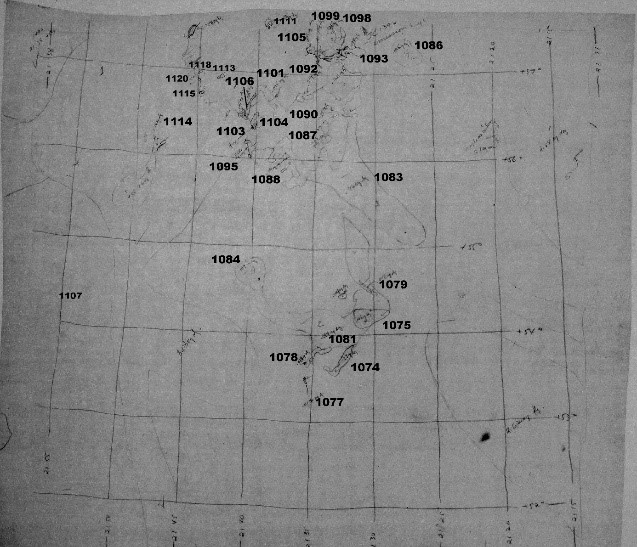

Beverly Lynds was so enthusiastic about the photos of the Palomar Sky Survey that in 1965 she also summarized the bright nebulae as the "Catalogue of Bright Nebulae" [5] and also listed dust and HII regions. Not only did she add the coordinates to the dark nebulae (both galactic and in RA and Dec), but she also gave the area and opacity of the dark nebulae (LDN) on a separate scale from 1 to 6, while the 1125 bright nebulae (LBN) gave color index (1-4) and brightness (1-6) – an incredible job, considering that there were no digital sources and that the evaluations of the photos were largely done by drawing through on tracing paper!

Beverly Turner Lynds died on October 05, 2024 and with her a great in astronomy. She not only created the above-mentioned catalogues, but also wrote the textbook "Elementary astronomy" published in 1962 together with Otto Struve and Helen Pillans and published many articles on astronomical topics. In addition, Beverly Lynds has always tried to make astronomy accessible to everyone – regardless of gender or origin.

She has passed on many of her books, photos and work to amateur astronomer and friend Rod Pommier, who is currently digitizing the outline drawings made by Beverly Lynds on tracing paper (all on the microfilm shown above) and assigning them to their respective LDN numbers. The project is due to be featured in Astronomy Magazine in July 2025, and Astronomy Magazine has promised to make the project available to all amateur and professional astronomers on the magazine website then - a great project! Good luck, Rod!

Our kosmos-os colleague Olaf Homeier motivated me to write this post with his wonderful photos of some dark nebulae. Here are some of his pictures:

From now on, my gaze will increasingly be on these particularly dark places in the sky, because it is precisely in these supposedly boring areas that stars with their planets and everything that develops on them are formed!

Special thanks to Rodney F. Pommier, M.D., Portland Oregon for the interesting exchange and the pictures sent. Rod's homepage: https://www.rodpommier.com

Literature on the topic:

- M. Völschow, R. Banerjee and B. Körtgen; Star formation in evolving molecular clouds

A&A Volume 605, September 2017

- E. Bergin, M. Tafalla: COLD DARK CLOUDS: The Initial Conditions for Star Formation

Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics Volume 45, 2007

Video on the topic:

- The Dark Side of Astrophotography – Rod Pommier – The Astro Imaging Channel TAIC

Sources:

[1] Barnard Catalogue 1919; Astrophysical Journal, 49, 1-24 (1919) https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1919ApJ….49….1B

[2] A Photographic Atlas of Selected Regions of the Milky Way https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/photographic-atlas-of-selected-regions-of-the-milky-way/EF03E04DC92CD2186244358C0545E935